Advocacy Gardening with Ecology Action

Small is bountiful and politics is dirty in the world John Jeavons wants all of us to digListen to John Jeavons, and you’ll never sniff at composting again. Jeavons (rhymes with heavens) is a garden activist. He grows crops, but more important, from his perspective, he grows soil. Compost is to soil what good food is to the rest of us. Through Ecology Action, a nonprofit group he heads, Jeavons spreads the word: Crops that feed people also can nourish soil, and from that deceptively simple fact springs a method of cultivation he believes can save earth, if not the Earth.

Photos by: Jim Bones.

Photos by: Jim Bones.

Once an aerospace and government-efficiency expert, Jeavons for the past 25 years has promoted sustainable agriculture to help reclaim diminishing arable lands worldwide. Though fluent in apocalyptic statistics about soil loss, global food deficiencies, and population growth, he shuns the label “doomsayer.” His aim is to demonstrate and teach a way in which each of us — whether a weekend gardener in Chicago or a subsistence farmer in Chad — can do an important little bit that, over time, could make a big difference.

On a steep hillside in rural Mendocino County, California, Jeavons and a few colleagues grow, by a practice they call minifarming, a prodigious amount of crops packed into 1¼ acres of once-poor soil. Minifarming reframes the collage of organic gardening methods developed by Jeavons’s teacher, the British horticulturist Alan Chadwick. The Chinese used similar methods 4,000 years ago. Later on, so did people elsewhere in Asia and in Latin America and Europe. The French have long depended on market gardens intensively planted in raised beds; the Irish, on their “lazy” beds, so named because the potato crop that comes out far exceeds the toil put in. Today’s related “biodynamic” gardening movement got its start in Germany in the 1920s.

Photos by: Jim Bones.

Photos by: Jim Bones.

The basic elements of these methods are: soil deeply dug to aerate it, encourage deep rooting, and permit close planting; regular composting; and the absence of chemical fertilizers or pesticides. Plants are closely spaced to save water, keep out weeds, and allow tending with simple tools. Plants that enhance one another’s flavor and health, such as bibb lettuce and spinach, are companion planted; those that weaken one another, like onions and beans, are separated. Organic farmers commonly use some aspects of these techniques. Even big commercial growers now plant a few crops, like baby lettuces, closer together for more efficient land use, and are investigating the economics of large-scale on-site composting.

Mechanized agriculture, with its dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, has resulted in declining soil fertility. Compared with naturally open-pollinated seeds, scientifically bred “Green Revolution” seeds produce abundant yields but, being genetically identical by design, are often more vulnerable to disease or pests that can wipe out an entire harvest. Biointensive minifarming, Jeavons avers, can restore poor soil and improve its fecundity while feeding people. “Properly used, it can build the soil up to 60 times faster than in nature. Yields can average two to six times those of U.S. agriculture.” In a refrain harking back to his high-tech days, Jeavons speaks of “miniaturization of farming” as a “paradigm shift akin in significance to the invention of the microprocessor.”

Photos by: Jim Bones.

Photos by: Jim Bones.

For Jeavons, small is not only beautiful, it’s also bountiful. “With minifarming, you can grow four times as much in a given area. The microcosm reflects the macrocosm. You’re preserving genetic diversity, freeing up land — I suggest that half the land be left wild. You plant heritage open-pollinates, like ‘Chadwick’s Cherry’ tomatoes or ‘Orange Jelly’ turnips, that are tasty and durable. You get higher yield and fewer insect and disease problems with venerable seeds. It’s something you can do in your own backyard. It’s good exercise, it’s beautiful, and you can design an action solution to global problems.”

Jeavons speaks and writes with the fervor of a 19th-century pamphleteer. How to Grow More Vegetables (1991, Ten Speed Press) and Lazy-Bed Gardening (with co-author Carol Cox, 1992, Ten Speed) are his best-known books. “His lineage is Alan [Chadwick],” says Wendy Johnson, former head of the organic garden at Green Gulch Farm in Northern California, and a student of Chadwick, “But his passion centers on saving the world. He’s interested in translating Alan’s specific agricultural practices into world health.”

Photos by: Jim Bones.

Photos by: Jim Bones.

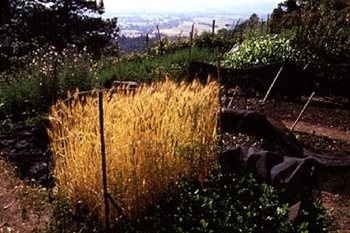

Meanwhile, back in the garden, pick up a clump of dirt and squeeze it. Good friable soil holds together, bound by sticky threads exuded by microbes, the work crew that maintains the soil’s living architecture. These and other tiny critters break down living matter that feeds plants, which in turn feed us and clean the air of excess carbon dioxide, making the oxygen we breathe and carbon, an essential fuel for plants and soil. “Seventy percent of the minifarm,” says Jeavons, “should be in carbon crops: corn, amaranth, millet, cardoons, sorghum [which gives kids a shady play area; later, the stalks make tepees], alfalfa, wheat, and poppies. The result looks like a Monet. You can grow enough wheat for a loaf of bread a week for a year in as little as two 100-square-foot beds. You need about 30 percent in calorie-rich root crops, too, like potatoes, turnips, garlic, and salsify.” In pure minifarming you don’t bring in fertility,you build it into the system. Many organic farmers truck in manure from feed lots and poultry farms. This makes for rich soil and lush crops, but in the long run, Jeavons argues, it’s not sustainable or ecologically economical, given the gas burned and the soil spent to feed the cows.

Minifarming relies on careful design, labor-intensive soil preparation, close planting, cultivation by hand, composting, and frugal water use. In developing countries where labor is cheap and plentiful, a family potentially could feed itself from the garden, grow extra food for income, and recycle crop debris to enrich the soil. While Americans rely on the supermarket, not the hoe, many gardeners like growing vegetables. “They are tasty,” says Jeavons, “and they’re vitamin bombs. Start with a salad garden, then a calories garden, then a carbon garden. For companion planting, things that go well in the salad bowl tend to grow well together. Lettuce tastes best if you pick it before the sun comes up. You can grow all the vegetables, strawberries, and melons in 100 to 200 square feet. You can grow 200 pounds of tomatoes. With dwarf fruit trees, 8 to 10 feet high, you can get 100 pounds of fruit per tree. Graft five heritage apple varieties on one tree!”

Now the dirty work: double digging, which involves spading trenches 2-feet deep across the entire bed. If this sounds like a scene from Cool Hand Luke, Jeavons says it’s a question of attitude. “If you think it will be hard, it will be. If the soil is too dry, you’ll need a pickax. Water the soil until it has just the right moisture content. If it is too wet, it’s too heavy to lift. Don’t use muscles; use your body weight. Lean on the spade; don’t push it or jump on it. Once you’ve built up soil structure, you need only loosen the upper 2 inches with a hoe.” That’s when you begin to see why Jeavons calls this a lazy bed. For composting, save fruit and vegetable scraps, tea bags and coffee grounds. Unlike bottle and paper recycling, home composting involves no gas expenditure, no recycling costs. Even if it’s your escapist plot, a small ecosystem goes deeper than pretty flowers and tender lettuce. “Globally, we need to grow soil,” says Jeavons, “to change compacted dirt into living sponge cake, and design beautiful gardens that breathe life back into our planet and ourselves.”

MAKE YOUR BED

Spring is the best time to start a bed. Mark it out with stakes and string, at least 3 feet square but no wider than 5, so you can reach the middle. If soil is hard and dry, water, weed, and let it rest a few days.

- Double digging: With a D-handled spade, dig a trench 1 foot wide and 1 foot deep. Put the dirt aside. Loosen the soil in the trench another 12 inches with a fork. Dig another foot-deep trench beside the first. Heap the soil from this second trench on top of the first trench. Dig on, transferring the top 12 inches and loosening the lower 12 , until the bed is complete. Rake it level, and spread over it an inch of cured compost. With a fork, sift together compost and 2 inches of topsoil. Don’t step on the bed! Compacting destroys soil structure.

- Composting: The ingredients of compost are both dry and green vegetation as well as soil. Dry matter (grass cuttings, leaves, straw, broken-up cornstalks) adds carbon, fuel for all living things. Green stuff (fruit and vegetable scraps, a few bones but no meat, compost crops) adds nitrogen. Don’t put in cat or dog manure, crabgrass, or diseased or poisonous plants. Soil contains microorganisms that aid decomposition. A layer of soil also keeps down flies and odors, and helps hold water. Turn the pile (to mix in air and moisture), add an array of materials, and a rich, fresh-smelling humus will cook up for next spring’s planting.

- Planting: Space seedlings evenly, so all roots find nutrients. Leaves trap carbon dioxide under their canopy where plants need it for optimal growth. Transplant seedlings in the cool of early evening. The crops in our cross-section grow well together by virtue of their differences: Shallow and deep roots don't compete; plants mature at various rates; and their edible portions are at different levels, both above and within the soil.